Rearticulating Free Software

Tuesday, 10 August 2021

Even important ideas get stale over time. They get reduced to platitudes and fixed expressions. Everyday application stops being about engaging with a point of view and is reduced to the repetition of ready-made idealogical building-blocks.

Even powerful ideas are at their weakest when this happens. On the one hand, it becomes harder to reason and recognize mistakes when reasoning. This can lead to two, simultaneous and contradictory effects:

People who defend stale positions try to reuse existing categories of analysis, and cannot by themselves evaluate the adequacy of new categories.

“Thought leaders” can introduce new ideas and approaches that are accepted on their face value. They might be worthwhile, yet most people find it difficult to coherently argue for or against these points, leading to dogmatic disputes that cannot be solved on the apparent level of the debate.

On the other hand, ideas become easier to attack. If a slogan is reduced from a summary to the stance itself, it becomes easy to find inconsistencies. The right attack can lead people who want to agree with a position to retreat into crude dogmatism. Detached from reality and reason, obscurity is the ultimate fate for any idea that stops living and becomes stale.

Personally I believe this is a big problem in a lot of political discourse. It might be the fear of questioning publicly held beliefs or it might just be the lack of interest to leave a comfortable ideological position. Either way, I see it pervade nearly every tendency of most every political category.

But that is not what I want to discuss in this text. Instead my focus is going to be on the topic of Free Software, which I fear might be sliding into staleness. I will be assuming a baseline familiarity with the subject, so please read the afore linked Free Software Foundation (FSF) article in case you are not familiar with the topic.

My position is that the only way to reinvigorate a stale idea is to re-articulate it. Start from the beginning and try to explain as much as possible from first principles. Re-articulation is always a personal matter, everyone has their own language and their own choice of words. In my case, I have a conservative approach and try to stay away from popular neologisms. This is in my opinion necessary, to appeal to as many people as possible. “Flavoured” language tends to create more conflict than is necessary.

Re-articulation is also always a dangerous position. It is easy to make a mistake, willingly or by mistake, and claim to have come to an entirely different position. It would be simple to claim “Free Software” makes claims about the price of software. Lucky, attacks on this level can just as easily be contradicted by engaging the existing body of thought, that will clearly state that “Free” is used in reference to freedom.

The goal of re-articulation is to have a reasonable account that explains your position, the unintended side-effect may be that an honest person must accept their position is apparently irrational.

I want to make clear, that I don’t make any claims of infallibility. I expect myself to be biased and lenient. I hope that people disagree with my ideas. I would like to engage in a constructive discussion, to refine my understanding. In this sense, I invite anyone to send me an email, so that hopefully both of us can come out of a discussion with a clearer picture of the topic at hand.

Perspectives

Fundamentals

To make clear what the subject matter is, I begin by clarifying what is conventionally meant by the term “Free Software”.

The authoritative definition of Free Software is summarized in the FSF Free Software Definition’s “Essential Freedoms”:

- The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose (freedom 0).

- The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1). Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

- The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help others (freedom 2).

- The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3). By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

We say Software is “Free”, it these conditions are satisfied.

Personally, I was always asked myself if it is necessary to phrase these freedoms in this form. It seems to me that freedom 2 and 3 could be summarised into one, something like

“The freedom to distribute modified or unmodified copies”.

My guess is that splitting this into two points is probably done for clarity’s sake, and would otherwise be an irrelevant difference.

(Update 27Dec21: It seems that “Four Freedoms” in a reference to a speech by FDR)

Control

A central notion in the essential freedoms seems to be that of control. “Control” in turn is the practical position of being able to make decisions in regards or for something.

Freedom 0 promises the ability to control the use, freedom 1 ensures control of the inner working. Freedom 2 and 3 are about not being controlled, or simply being “free” to share immaterial objects (software).

It should be noted that this freedom is presented as unconditional. No contracts, no academic degree, no membership, no nationality, no age requirement, etc.

Take the non-programmer. The four freedoms are not immediate, as he cannot make use of them by himself. He either requires further education or has to know how to make use of his freedoms. As such freedom becomes conditional.

A step further is when software is written in a language one either doesn’t understand or can work with (e.g. due to broken or inaccesible tooling). This is a practical impediment upon software freedom, even though formally I might be able to exercise these.

Overall, it seems that it’s easy to say when someone has control, but more difficult to draw the line when this is not the case. But does this matter? One might compare this to reading a document in a foreign language. If you don’t understand English, it will probably be easier to find out what it is about as English is a popular language. Something written in Manx on the other hand will be harder to comprehend. My best attempt at a general claim would be: As a rule of thumb, the practical restrictions on software freedom shouldn’t be seen as infringements, but cases can be imagined where it turns out to be an issue.

I believe that control, just in itself is universally attractive. There should be no rational reason to decline control, with all else staying the same. This is because control does not have to be active, doing nothing or delegating control doesn’t mean loosing control. Nevertheless, it might be too simple to conclude the ability to control is always meaningful.

So while the individual might always want control, it should be clear that everyone cannot want everyone to have control over everything. The simplest examples might be using parental control to prevent children from breaking. More complex examples might be found in academic or corporate environments, where the software restrictions reflect the restrictions of the environment itself. The most popular example is of course the control required to make money by selling software. One might want to say that these forms of control are in themselves illegitimate, but I hesitate to claim this generally or in the context of this text.

Finally, we can distinguish between two forms of control:

- Passive control, where the software intentionally limits its user as designed.

- Active control, where software has a super-user (usually whoever develops or distributes it) who can speak for or even override the actual user.

Two simple examples: Passive control is seen in a printer that refuses to print if any cartridge is empty, even if there is black ink and the document is greyscale. Active control is when a corporation like Apple can remotely remove software from a device.

Ethics

An argument can be made that Free Software that respects the user’s freedoms is more moral. A sketch of a Kantian argument in form of a Categorial Imperative might look like:

One should not strive to exercise control over others using non-free software, as one couldn’t rationally want to others to control oneself using non-free software.

A utilitarian might want to point out that with more people having access and permission to improve/distribute the source, the utility of software can be improved for everyone, making it preferable to non-free software.

I don’t think that this is an argument that would make anyone change their mind, nor that it is particularly convincing.

Still it is common to see discussion phrased in terms of ethics or moral values. Proprietary, that is non-free, software is regarded as non-ethical, free software as ethical, by virtue of the software freedoms is ensures it’s user.

Personally I do not think that this is the most productive framing. I do not think that proprietary software is written out of hatred for users in principle, or that control is always exercised for nefarious reasons. It can be, but that doesn’t suffice in my eyes to make a good ethical.

Licenses

In most cases, software freedom is encoded in the form of licenses. This doesn’t have to be the case, as when I were to give a friend of mine some software I wrote and tell him to do as he wishes. We both assume sincerity in this action, and don’t require an arbiter to ensure this freedom.

To assume this in the public sphere is more difficult. It is certainly possible, but especially on the internet it becomes a lot more difficult to trust just anyone. In this sense, Free Software licenses encode the promise of software freedom in relation to the state.

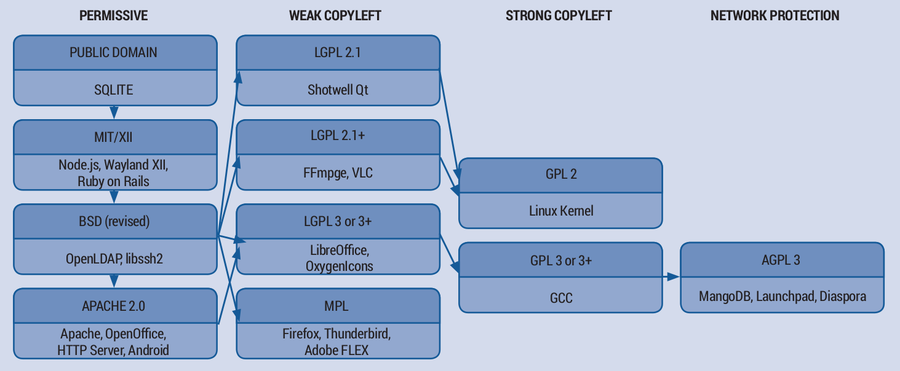

In practice, licenses are roughly divided into permissive (BSD, MIT, …) and copyleft (GPL, EUPL, …). Both promise freedoms, but differ in terms of distribution, and the insistence on “inheriting” the terms under which the software is distributed further.

There has historically been some debate over which is preferable. Permissive licenses are seen as less restrictive and complicated to understand. “Certainly these must be more free, as they restrict me less”, their proponents claim. Copyleft on the other hand claims defence by insisting it ensures “downstream” freedom, ie. not of the developers but of the users is ensured.

Personally I am not too invested in these arguments. My line is that the more effort I put into a project, the more copyleft it becomes. But this is more of a preference than a hard-line. Generally I am not too interested in the legal aspects, as long as they provide a solid groundwork for distributing public software.

The reason I even mention the legal aspects of Free Software is due to the recent discussions about variations of Free Software (more commonly refereed to as “Open Source” in this context, though the idea is roughly the same). The most prominent examples are so called “Ethical Software Licenses”, that prohibit use based on ethical grounds. A short overview can be found here. Perhaps satirical, but certainly much worse are ideas like the “Aryan Public License”, that prohibits “People of non-European origin or black skin Colour” to use the software. My intention is not the equate these two ideas, I can certainly sympathise with the idea behind ethical software (one does not want to be associated with harmful phenomena), while the idea of restricting the use of software to arbitrary groups is replant, no matter how vague or precise.

I do not know how popular these licenses are. It seems there is more discussion about them then actual usage. Nevertheless, I find myself disagreeing on principle. Free Software is often associated with the slogan

“Free as in speech”, not “free as in beer”.

indicating that Free Software is a matter of liberty, not price. The comparison with free speech is topical1: It might be probable that if you were to pick a random number of instances in which “free speech” applied, you would see more harm being done than good. You will see people spreading lies, perpetuating outdated stereotypes, engaging in dishonest discussions, etc. The same will apply to other liberties such as the presumption of innocence, freedom of press, freedom of movement, to varying degrees. The claim in defence of these much abused privileges is that those situations where it does matter outweighs those where they are abused. Any limitations upon said freedoms are said to be a risk infringing this principle.

The same applies to Free Software, albeit to a less fundamental degree.

Fundamentally, these license take issue with Freedom 0, the freedom to use software for any purpose. To remedy this, an attempt is made to exercise control over the user, in form legal form. This is interesting, as compared to traditional proprietary software, software distributed under ethical licenses are usually relatively permissive, except for their distinguishing feature. As a user, I have the practical freedoms that any other license may grant me. Traditionally proprietary software would actively limit the user, distributing programs in binary or obfuscated form, requiring license keys, protecting itself from backwards engineering, etc. This software (or rather its copyright holder) actively tries to protect itself. Software under ethical licenses can be used for any purpose, modified, extended, improved or even abused.

As I have implied at the beginning of this section, licenses are not to be confused with the software itself. It is easy to confuse the legal realm for reality itself. E.g. when analysing an economy, one has to realize that neither its black market nor its historical, geographical and historical cannot be imagined away.

This appears to be a issue for Ethical Software, as its goals are

encoded in the license it is distributed under. It might therefore be

more effective to make the control more explicit: A native attempt might

use a “Kill-switch license”, that might be as permissive as any other

license, but prohibits the modification or inhibition of the

functionality indicated between the lines indicated by

KILLSWITCH START and KILLSWITCH END. This

section would allow any program to be inspected and controlled remotely,

making sure that any violation of the intended terms can be swiftly

punished. This of course is naive, as it would rely on the legal terms

to have the kill-switch work. A more sophisticated attempt might use a

programming language that must a kill-switch injecting compiler. Even

simpler would be publishing the software in pre-compiled form, with our

kill-switch that ensures it is operational. Of course, at this point we

have for all intents and purposes become everyday proprietary software.

But it must certainly be great software for people to use it despite

it’s unusual demands.

All of this hypothetical, and more fun to write than productive. A more serious point can be raised when considering free software under the same point. Does its aim, namely the promise of user freedoms rely on the legal framework of licenses? It depends: Permissive licenses are hard to break, as they restrict you less. Usually the bare minimum is the requirement of attribution, which arguably is not the goal of the software itself, even if it might be regrettable from a personal point of view. Copyleft on the other hand intends to ensure software freedom “virally”. When someone ignores the terms of the license, and distributes an unattributed, proprietary versions of the software, this aim is missed. Of course, in both examples the intention to grant users software freedom is lost on the downstream users.

I take this as an indication This is an indication that the legal framework of free software is a necessary but not sufficient condition for free (public) software. The way to protect yourself from unintended limitation of free software should be fought for on both the level of public consciousness and design. The law can help, but more often than not I fear that no matter the license, it is hard to ensure the legal demands. Most individuals do not have the means to pursue offenders, and I suspect that if someone intends to break the terms, they can also do a good enough job of hiding it.

Developments

Free Software was first articulated in the 1980’s in the context of academical departments. It is said to exist before that point, just not formalized in the language we use nowadays.

Even though “only” 40 years have passed since the 1980’s, a lot has changed in the world of computing. The two central tendencies have been the increasing portability of computing devices (personal computers to laptops to smartphones) and the increasing importance of networking over raw computational power.

I have previously commented on the shift towards personal computing, and while it makes computing more accessible, this has come at the cost of more complicated hardware. This is a problem for free software, as often specific hardware requires proprietary drivers to well work or work at all.

Computers used to be big, shared and complicated machines, found in academical departments or corporate buildings. The personal computer challenges these preconceptions: They are obviously a lot smaller, are used by one or just a few people and should not require a degree in computer science to operate.

This image was invoked by Apple, in an attempt to market their easy to use Macintosh line, that doesn’t require you to learn anything more than how to use a mouse. The Macintosh was simple though, no networking, only one application ran at a time and it did not have multiple decades of legacy cruft. To my knowledge, not even the Apple II was supported.

Modern day computers turn out to be a lot more complicated. The risks of computer viruses and other scams are motivated by the intent to steal information, prevent users from using their devices, or with the rise of Cryptocurrencies, even just to use computing power. While I think that we should question how little knowledge we should assume people to have for them to operate computers, the reaction from eg. Microsoft is to force updates because the average user cannot be trusted to maintain their computer for themselves.

As an issue, there is little that can be directly addressed. The best one can do is to ensure that children are given proper education on computer usage and security.

Yet this development is not that drastic. In some sense, the individualisation of computing makes software freedom more immediate, as all the users are just you.

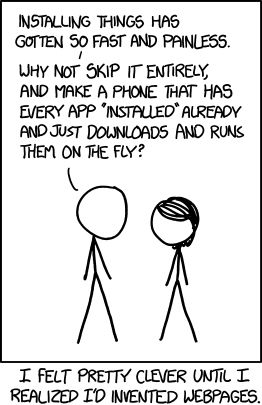

The more interesting shift came with the world wide web, specifically “web apps”, ie. services that are provided through web browsers. Compared to the classical computer service, where a client would communicate with a service (eg. Mail), the web “downloads and executes” the client on-the-fly.

The issue here is that for the user the program comes into existence as requested, and disappears when it is finished. While it is sometimes possible to inspect what is going on (eg. when frontend Javascript code is non-obfuscated), there exists no general, meaningful way to change what the software does, as this is not how the web was designed to work.

The FSF suggests that websites provide stability guarantees for their website structure and the Javascript code that is executed. The idea, to my understanding is that patches can be applied and distributed with some sense of security, to modify the behaviour of what is run in the browser.

As is requires active cooperation from the webmaster’s side, it appears to be a rather fragile solution, considering that those sites engaged in undesirable behaviour the user would want to change, (tracking, advertisements, popups, …) are exactly those, have no incentive to offer such guarantees.

Many lament the web has lost it’s way. They scoff at the concept of a “turning complete document system”. As a full-time contrarian I find it hard to agree. I have previously written on how the web is an expression of the limitations of regular abstractions that most operating systems operate under. Especially since Google has become the de-facto standardizer of the Web, it has been possible to advance and clean up the previously fragmented landscape, making browsers a flexible component of most modern computer systems.

Setting aside the clumsiness and inefficiency this usually brings along, the main issue is that the purpose of the web is just not what it used to be. The reality of the matter is that we have shifted from a simple, hypertext system found interesting by scientists to a complicated, multimedia distribution system that is pushed by the very entities the personal computer and (near) zero-cost distribution threatens to challenge.

Considering how the interests motivating the development of the web have changed, it is not that much of a surprise to see the effects.

The second major shift came with the rise of mobile computing. Compared to the rise of personal computers, that was somewhat “open” and “standardized” (Who cares if you monitor was produced by Compaq and your keyboard by Dell?), the smartphone and tablet world grew up far more constrained.

Did it have to be this way? Perhaps not. An Android video demonstration 2007, has Google co-founder Sergey Brin saying:

Just like how I learned how to write great services and software upon free tools for the web, like Linux and GNU, now with Android you’ll be able to do the exact same things on mobile phones.

The software is all free, the source is completely available, and we expect great new powerful applications to be developed on it.

The mere mentioning of GNU surprised me, but as anyone who is familiar with Android from both a user as well as developer perspective knows, things changed: The system is tightly regulated, most user-facing software is not free and privacy concerns are widespread.

As for the other member of the mobile-duopoly, Apple, it is unsurprising that they never had aspirations of this kind. After all, the implicit deal that Apple makes with their customers is to play Hotel-manager, while the users are taken care of in their carefully curated “computing” environment: “You cannot change X, but you don’t have to worry about X either”, is the premise that many find attractive.

All of this leads to a very clear user-developer dichotomy. You either interact with a smartphone as a user in it’s “regular” mode, or as a developer with the help of a “real computer”. I argue this dichotomy is real but accidental, but I will continue this though in the next section.

On may therefore ask themselves what the cause of these shifts are? A popular, yet for my taste too simple answer is malice. Microsoft, Apple, Google, etc. are maltreating their users out of spite and ill intentions. Not only is this overly simplistic, the issue is that this constructs a framework of analysis that tells you that all you need is a megacorp with the right values to prevent this kind of behaviour. Google giving up on their “Don’t be Evil” slogan is seen as a moral shortcoming.

While probably more complex, my best general guess is a mix of real needs and opportunism. As I have mentioned before, it seems true that for better or for worse, most users cannot be trusted with the responsibility of administrating their own tools. In absence of any other solution, this task is passed on to the organisations developing and maintaining the software. And as it happens to be, this position is exploited – mostly for financial interests – leading to the behaviour so many object to.

Regardless of the details, motivations or the specific history, we recognise that these developments dictate the norm and our expectations of how computing looks like.

Outside of the norm, we find the free operating systems. Despite the wishes of some people, we shouldn’t assume that this is the default, or that this is the realm most people encounter first. In almost all cases, it is my impression that people are guided towards Linux, GNU, BSD or other free computing environments under the guidance of someone more knowledgeable, an evangelist of sorts.

While the commitment and enthusiasm on the topic of software freedom might vary from group to group2, most will to at least some degree acknowledge the influence that software freedom plays in the development and nature of these systems.

What I find interesting, is to what degree the user can relate to this. One does not seldom here of people who find, some Linux distribution to be more of a chore, not worth the effort. By necessity, free software operating systems have less manpower, fewer/weaker links to the hardware industry, it seems impossible to avoid issues. But if all there were to these systems is less polish and reliability, and on some theoretical level an access to the software, what would be the point?

Some might want to say, that the concrete implementations are preferable: XFCE works better than Windows’ UI, KDE can be better customised than macOS, etc. But these matters are contingent, the specific options a user is provided is not a matter of software freedom. Windows might just as well have had a XFCE-like UI. macOS might allow for more customisation and more options. But these wouldn’t be substantial changes, beyond a design decision. One should not confuse “programmability” for software freedom. The traditional Unix operating system was pretty programmable, but certainly wasn’t free.

The critical difference that free operating systems should provide is the invitation and the encouragement to make use of granted freedoms.

Again: Does the average user notice? I don’t think so, nor

does the system provide the proper ground to encourage and assist the

user to this end. Setting aside that most people do not have the

background to understand and change the software they use, let as assume

a user wants to modify a program they use, say something simple like

wc, to give you an estimate of how long it would take to

read some file, by dividing the words by the words-per-minute a user

reads.

Assuming a GNU system, we might think of running

$ man wcthat points the user to https://www.gnu.org/software/coreutils/wc. One then has

to notice that wc is part of the “coreutils” package. Looking around,

you’d eventually stumble upon the project website https://www.gnu.org/software/coreutils/, and redirects

you to the source, located at https://git.savannah.gnu.org/cgit/coreutils.git.

Stumbling around the file hierarchy, you’d eventually encounter https://git.savannah.gnu.org/cgit/coreutils.git/tree/src/wc.c,

the source for wc. At the time of writing, this file is 999

lines long.

Maybe a few dependencies are missing, a build-tool or two. This too can be figured out, eventually.

There is a lot going on, but eventually one would understand the

structure, where to start modifying and how to implement your feature of

interest. Having done so, the question becomes how to install it. One

might not have the permissions to replace /usr/bin/wc with

your own build, and even if one did, the package manager will probably

override it at some point. The alternative would be to install your

personal wc in a private executable directory, and adjust

$PATH to take it into account. The downside here is that

you have just burdened yourself with manually maintaining another

program.

Some distributions are better in this regard. Debian e.g. provides

apt-get source [package name] to download and prepare

everything the user needs to work with the software. You might change

what you want, generate a package and install it. But this still means

the user now has to deal with managing and upgrading the software by

themselves, fighting against the package manager.

Things get more complicated, when we stop talking about something as

small as wc, but instead consider a GUI program. Let us say

one wants to remove an annoyance such as a window that unintentionally

pops up. Here to, one has to acquire the source, set up the environment,

ensure the dependencies, and proceed to investigate. Maybe one starts

from the main function, maybe one tries to find a string

contained in the popup, and using clever development tools tries to

track where it is used. Perhaps a debugger might help to trace what is

going on.

Either way, it is usually a lot more difficult than just right-clicking on a UI element, opening a context menu that say “Show Source”.

Spirit

As I have previously indicated, the legal aspects of Free Software might be categorized as “necessary but not sufficient”. Free Software shouldn’t just satisfy the four freedoms formally, but live them.

As an analogy, reconsider the civil liberty of free speech. While default in most western democracies , there is a fair point to be made that it is not “lived”. Just consider the controversies over the last few years on the topic, between “Free Speech Absolutism” and the “Anti Hate-Speech”-Movement. Merely mentioning the topic is certain to prompt hesitation in some readers. I can relate to this, and I too have been wondering whether or not to even give this example… The idea I wish to highlight it the distinction between intent and use. While almost nobody will deny that the freedom of speech is made use of to lie, deceive and manipulate, the intent is to protect the proliferation of truth, against adverse interests. In this sense, “living” freedom of speech is the pursuit of truth and the active interest to be refuted. It is fair to say that this is not given, both by the “abuse” of FoS (which cannot be distinguished from genuine use) by some, and the deserved caution of others. A legitimate argument can be made that lived FoS is not practicable, given the circumstances of out societies, but that is a different discussion.

Assuming this perspective of intend vs use, what would “living” software freedom look like? It might be easier to consider what the formal satisfaction of user-freedom looks like: Think of software that just dumps it’s source sporadically, without documentation or much other consideration. Think of software that is hard to read or change, and generally suffers from invisible code-dependencies. Think of software that depends on a specific environment, non-free dependencies that prevent it from being meaningfully shared.

To me the distinction between “Open Source” and “Free Software” might fall along lines like these. While Open Source can be seen as the analogy of proprietary Software with accessible source code, Free Software shouldn’t just be a drop-in substitute. This is to say, that to be Free Software has an implication on the design of the software itself.

Big Monoliths, such as Browsers, Word Processors, Desktop Environments or even Operating System Kernels are usually harder to introspect, to understand and work with. As such, our control is more abstract. But even in a fully free GNU operating system, you cannot just run

$ src wcto update a system component, at least not without some effort.

One aspect of Free Software is the consciousness of the freedoms it entails. One might know that some software is free in the same sense as one knows that the moon revolves around the earth. But just like looking at the moon during a clear night and consciously realizing that there is a giant rock moving around a more giant rock, surrounded by practically nothing, the fact that you can make decisions about the software you use might not be immediately apparent.

As such, it seems that in practice this aspect of free’ed software is lacking the potential to melt away the boundaries between programmer and user.

Note that this doesn’t have to mean everything getting more complicated, more technical and more rough. I an imagine that an authentically free software environment shouldn’t be based on our current paradigms of machine-user interfaces. It might be that graphical programming becomes more sophisticated, or that programming languages become more expressive, lowering the requirements needed to operate them. Just as free speech doesn’t mean everyone has to have an opp ion about everything, nor does free software mean that everyone has to program everything.

Privacy

Free Software is usually associated with the concern for privacy and security. The usual argument implies that if the software cannot be studied, it cannot be independently verified, hence it might be insecure.

Assuming that to be the case (I don’t necessarily), this really only requires one freedom, namely to study the source. It is rarely recommended that users work on security critical sections of their code without the proper background. Would you install just any patch to a cryptography library a friend might have gave you?

Nevertheless privacy and security remain an important talking point in free software advocacy. Popular proprietary software is denounced as in inherently being (at the very least potential) malware, because the opposite cannot be proven. And I do not want to deny this can be true, especially for Whistleblowers and in general people outside of the law3.

Yet while important one should also acknowledge that this line of argumentation is meaningless for most people. I personally speculate that there is a kind of correlation between the personal importance of privacy and a mistrust of (for lack of a better word) “institutions of power” (the state, corporations, etc.). If one fundamentally believes that these share the same values and interests as oneself, there is less of an interest to defend information and control others are less willing to give up.

If this is true, it would mean that every discussion about privacy and the relation between free software and privacy are a proxy argument on the justification of mistrust. And as it is usually the case with proxy discussions, you either have to dive deeper or it becomes an inefficient and tiresome mess. At the same time, the deeper discussion is more controversial and complicated.

It is therefore that I think the emphasis should shift away from privacy to topics I have discussed in previously (personal control, adaptability).

Summary

I force myself to end the text here, even though there is still more to be said. My hope is the return to a few questions that could be further discussed using the examples of concrete questions.

To summarize, my intention was to articulate a understanding of Free Software that mirrors my impressions and aspirations. The main points were:

- Free Software is a necessary tool for computational autonomy (or the self-emancipation of potentially heteronomous/fremdbestimmte relations).

- Both the ethics and privacy formulations for the necessity of Free Software might be less productive that it is commonly taken to be.

- While important in their own right, the horizons of Free Software should not end at licenses

- Not enough emphasis is placed on “practical living” of Free Software (both in an individual and social sense) and the ultimate dissolution of the user-programmer dichotomy.

Finally, to reiterate my introductory request: As I am fascinated by these discussions, I invite anyone – agreeing, uncertain or disagreeing – to talk about these questions with me in private correspondence. My only request is to do so in good faith, as I (perhaps naively) tend to assume the same when talking with someone. If these turn out to be interested, it would be nice to publish these in a curated form for others to read.

It should be pointed out that freedom of speech shouldn’t be equated with the freedom to say anything anywhere. My understanding of free speech is the permission to defend any idea, not in any form. The requirement to be silent in a library does not infringe upon free speech.↩︎

Some might place more emphasis on security, others on low hardware requirements.↩︎

In these cases Software Freedom is probably not enough: For real software safety, one also requires hardware safety that is increasingly difficult to ensure.↩︎